“Halt and Catch Fire” makes the world of 1980s computing compulsive viewing

Source: J.D.

NO matter how you film it, the beige, functional Commodore 64 computer will always seem less glamorous than Knoll office furniture and the swinging 60s. Compared with “Mad Men” or “Masters of Sex”, a 1980s tech start-up seems lacklustre material for a drama. Yet “Halt and Catch Fire” (a term for computer code that causes a CPU to stop working), which follows a rag-tag group of computer engineers in Silicon Prairie, has been one of television’s best offerings for three seasons now. Its third ended earlier this month; AMC has announced that the fourth season will be the last. The disappointment of fans and critics is tangible; there is no show that reckons with technological innovation—and the people responsible for it—quite as effectively.

NO matter how you film it, the beige, functional Commodore 64 computer will always seem less glamorous than Knoll office furniture and the swinging 60s. Compared with “Mad Men” or “Masters of Sex”, a 1980s tech start-up seems lacklustre material for a drama. Yet “Halt and Catch Fire” (a term for computer code that causes a CPU to stop working), which follows a rag-tag group of computer engineers in Silicon Prairie, has been one of television’s best offerings for three seasons now. Its third ended earlier this month; AMC has announced that the fourth season will be the last. The disappointment of fans and critics is tangible; there is no show that reckons with technological innovation—and the people responsible for it—quite as effectively.

While breakthroughs in computing technology—the PC clone, the dial-up gaming community, anti-virus utility—ostensibly keep the narrative moving, it is the camaraderie and the betrayal of characters that makes “Halt and Catch Fire” heady viewing. Rival philosophies clash. Loyalties, professional and personal, are tested. As in “The Social Network” and “Steve Jobs”, it is not the bytes themselves but the humans who are compelled to experiment with them, that draw viewers in. “Halt and Catch Fire” paints a realistic picture of flawed characters and shows us, too, that the innovators are not always rewarded with fame and Hollywood biopics. In the fast-paced tech landscape, the creation can become quickly defunct and its creator left in the shadows.

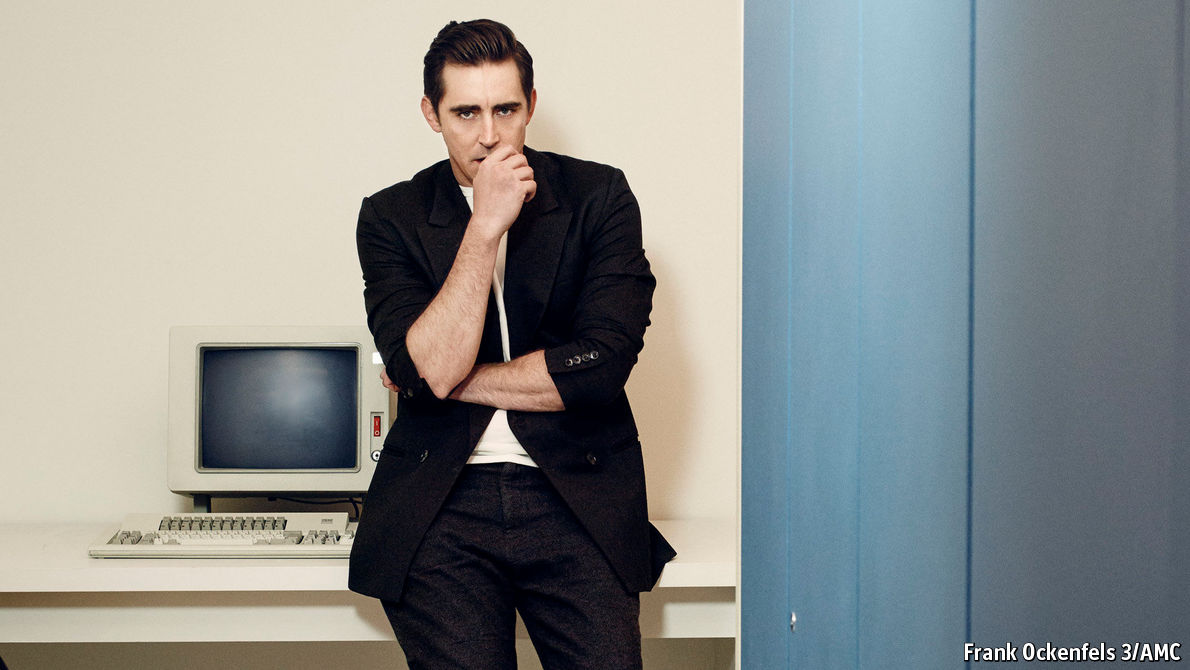

The series largely revolves around the fraught alliance between a corporate rebel, a tightly-wound engineer and a punk programmer. Joe MacMillan (Lee Pace), an exile from IBM, recruits an ego-bruised engineer to devise a cheaper PC clone and a gifted computer engineering student with attitude to write its code. From there, we see their endeavours spin-off into start-ups, product launches, acquisitions and IPOs, but often without any signs of clear victory. Indeed, “Halt and Catch Fire” continually interrogates what defines success in tech, in business or in life.

Leading man MacMillan is as enigmatic as he is magnetic. His light burns so bright that, despite feeling professionally betrayed by him, engineer Gordon Clark (Scoot McNairy) admits he misses Joe’s knack for making each collaborator feel like his best friend. The connection and contrast between MacMillan—clearly modelled on inspirational tech gurus like Jobs—and the volatile programmer-turned-CEO Cameron Howe (MacKenzie Davis) is well drawn. His futuristic vision sets him on a quasi-spiritual quest for the next big thing, while Howe’s version of the digital revolution is personal, community-based and coded from the ground up. They rarely see eye-to-eye, but “Halt and Catch Fire” highlights their shared idealism and ambition to define the future. For that, they are inextricably bonded.

The show is revelatory in its examination of the Garden of Eden of personal computing. It breathes life into the oft-impenetrable world of the internet, social networks, programming, online commerce and video gaming—activities often dismissed today as absurd and dehumanising. There, in that beige box, “Halt and Catch Fire” suggests, is where the world we live in today was shaped. It tells a story about why these things were created and what they offered in the first place. We see the impulse to buy and sell, chat privately and snoop on users emerge as a start-up expands to hundreds of thousands of members. Even viruses and their antidotes are shown as the inevitable result of our urge to explore, tinker and sell security. In “Halt and Catch Fire”, technology is simply an extension of human instincts, a vehicle for our deepest wants.

What is particularly impressive is that the drama never shies away from the technical when pursuing the personal. Its inclusion of ARPANET in a plotline, for example, doesn’t confound; we understand it to be the precursor to the internet. It makes sense, too, that a code that gauges the size of a network could be the foundation for anti-virus software. And it refrains from scapegoating technology: “Halt and Catch Fire” is clear that it is not microchips but human behaviour—our attitudes towards success, work or family—that alienates characters from one another.

One doesn’t need BASIC programming to be subtly moved by “Halt and Catch Fire”. Howe is most fascinating when she is grappling with the mixed blessing of leading, not when she is sat typing lines of code. We feel most sympathy for Clark when he soothes his marriage woes by searching for anonymous human connections on Ham radio, not when he is installing servers. MacMillan’s genius lies in beguiling an audience with the possibilities of technology (he can’t code to save his life). Anxieties about the social repercussions of modern technology have become clichéd. “Halt and Catch Fire” serves as a healthy reminder that when we scratch beneath the touchscreen, we’ll see ourselves.

| }

|