There's no point resisting corporate websites. It's time

Source: David Mitchell

Information is far from free. Just ask Phyllis Pearsall. She was the woman who drew up the London A-Z by pacing the streets with a notebook for months and months. Or so they say. Sceptics point out that her father ran a cartographical firm that also produced map books of London so she might have benefited from a head start. But, whether obtained through inheritance or shoe leather, her company has been selling that information ever since. These days, you'd just use a satellite.

Information is far from free. Just ask Phyllis Pearsall. She was the woman who drew up the London A-Z by pacing the streets with a notebook for months and months. Or so they say. Sceptics point out that her father ran a cartographical firm that also produced map books of London so she might have benefited from a head start. But, whether obtained through inheritance or shoe leather, her company has been selling that information ever since. These days, you'd just use a satellite.

Hang on, though �C I may be getting a bit complacent about infrastructure. There should be no "just" when it comes to satellites. Whatever mankind's technological advances, it's still much easier to get people to walk along thousands of streets writing things down than it is to build a satellite equipped with a high resolution remote-controlled camera, attach it to a rocket and then launch the rocket into space along with people and/or robots capable of positioning it with sufficient care and accuracy that, not only can it photograph the earth clearly enough to discern all the streets of a major city, but it can transmit those images reliably back to the ground. That's literally and metaphorically rocket science.

Like Pearsall, Google understands that, with data, you've got to speculate to accumulate. That's why it undertook the vast and expensive information-gathering enterprise of sending thousands of Street View camera cars in her footsteps. And not just in London, but over about a third of the world.

In 2010 it emerged that, in Britain at least, Google hadn't restricted its car-borne information gathering to photographing buildings, but had also hoovered up other data from whatever unprotected Wi-Fi networks it passed. Those nosy cars were peering past the net curtains to find our darkest secrets: our passwords and porn preferences.

Google said this was an accident caused by an over-zealous piece of software: "We were completely unaware of PeepingTomBot 4000's actions. This confused but well-meaning artificial intelligence developed an obsession for understanding human masturbation as part of its quest to become a real boy."

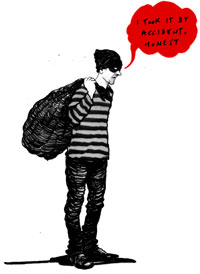

That was not Google's statement. But it did say the data had been collected by accident and would be deleted, unread. This was accepted for various reasons: first, Google is incredibly powerful and can do what the hell it likes so it's nice that it even bothered to say sorry. And second, computers are such a mystery to most of us that the implausibility of the explanation �C that this information had been unintentionally collected, like dog shit on a shoe �C didn't bother us. "Who knows how these things work anyway?" was the feeling. "If some billionaire techies tell us it was a mistake, we'd better believe them. Just like we'd believe them if the crown jewels were found in their house and they said it was the accidental consequence of going round the Tower of London with a magnetic key ring."

But, according to the US Federal Communications Commission, we may have been wrong to accept Google's counterintuitive excuse. It found that the Street View software had been explicitly designed to harvest private data by an engineer who kept warning bosses about this very fact. Which would mean that Google was guilty of premeditated theft.

You may think "theft" is a strong word for covertly copying people's information: no one has been deprived of anything they previously possessed. If you duplicate someone's porn bookmarks, they've also still got them. But, in Google's line of business, I don't think you can deploy that argument. In computing, everything is copyable: if I illegally pirate Microsoft Word, I haven't deprived Bill Gates of anything. He still has Microsoft Word �C he doesn't have to type his love poetry into the text bit of a spreadsheet �C yet I have stolen a little part of that organisation's ability to do business. And Google must be more aware than any other firm that knowledge of people's web surfing habits and purchase preferences has a cash value.

This is the issue over which we, the public, and they, the rapacious corporations, need to get down to brass tacks. They desperately want our information �C our likes and dislikes, our habits, our secrets, our purchasing power, where we live, who we know. Future prosperity, as intuited by Google, Facebook and indeed the Guardian Media Group, relies on ever more cunningly targeted advertising. Their services are free, so what do they have to sell if not our data? The internet's continued function requires wires and satellites and warehouses full of humming servers and cars driving down thousands of roads. To pay for this, websites want to flog the perfect advertising space to each customer. If you're a new vegan smoothie bar opening in Hoxton, they want to offer you access to the screens of exactly the right two dozen local dupes.

We're divided in our responses to this. Some unthinkingly share everything about their lives from their relationship status, through drunken pictures of themselves, to their opinion on a new chocolate bar. They want to yell their identity in a continuous screech of affirmation. Others are mindful of the new media saw that if something's free then you're not the customer, you're the product.

Oddly, I think the former group get a better deal. They receive something in return for their information: an activity they enjoy. Meanwhile the latter bunch are stuck. It's increasingly fruitless to try and withhold everything about yourself from the ruthless corporate grid. You still get bombarded with advertising, but for things you definitely don't want. I've hardly bought anything from Amazon except birthday presents for some very different friends �C yet I still get recommendations. Insanely eclectic recommendations: the complete Steptoe and Son, all of Westlife's autobiographies, the libretto of Salad Days and a long-handled hoe.

There's an irresistible market for our data but that doesn't necessarily make us the product �C it could make us traders. Corporations like Google shouldn't extort information secretly but neither can consumers withhold it at all costs. The parasitism of corporations snooping on us could become a symbiosis, in which information is freely surrendered in exchange for something concrete: say a garden gnome. Or, you know, adverts that are actually useful because they offer things we want to buy and ways of doing so more cheaply.

This is the difference between a market and a war. In a war, if the other side wants something you've got, you definitely want to withhold it. If that happens in a market, and if you can strike the right deal, it's an opportunity to make everyone better off.

| }

|