From Altair to iPad: 35 years of personal computer market sh

Source: Jeremy Reimer

Back in 2005, we charted 30 years of personal computer market share to show graphically how the industry had developed, who succeeded and when, and how some iconic names eventually faded away completely. With the rise of whole new classes of "personal computers"―tablets and smartphones―it's worth updating all the numbers once more. And when we do so, we see something surprising: the adoption rates for our beloved mobile devices absolutely blow away the last few decades of desktop computer growth. People are adopting new technology faster than ever before.

Back in 2005, we charted 30 years of personal computer market share to show graphically how the industry had developed, who succeeded and when, and how some iconic names eventually faded away completely. With the rise of whole new classes of "personal computers"―tablets and smartphones―it's worth updating all the numbers once more. And when we do so, we see something surprising: the adoption rates for our beloved mobile devices absolutely blow away the last few decades of desktop computer growth. People are adopting new technology faster than ever before.

Humans are naturally competitive creatures. Not only do we compete with each other for money and power, but we form strong allegiances to various tribes. Whether it's a favorite sports team or a chosen computing platform, we passionately cheer when they win and feel a punch in our guts when they lose. Companies know this, and they will trumpet their successes and quietly hide their failures. But is it any more important to want one multi-billion dollar company to win over another than it is to root for one arbitrary multi-million dollar athlete? Is it anything more than cheerleading?

Well―there's certainly plenty of cheerleading, but tracking the rise of fall of market share over time has more serious uses, too. Software developers need to keep track of market share so they can decide where to invest their resources. Consumers may then choose platforms based on software availability. Platforms can live―and sometimes die―by market share. The successes and failures of one generation of platforms affect the next, and ultimately this has an impact on everyone's digital lives.

Certain lessons from the past can also be applied today, and may even foreshadow what the future holds.

So what is market share?

Market share is typically defined as the percentage of a company's product compared to the total of all products sold in that category over a given period of time. For example, if Pepsi sold 25 percent of all brown carbonated soft drinks in the third quarter of 2010, it would be said to have a 25 percent market share for that quarter.

This sort of measurement works well in the beverage industry. The product is inherently disposable and shifts in market share are small. When you move from carbonated sugar water to the computer industry, as former Apple CEO John Sculley did in 1985, things get considerably more complicated.

In addition to market share, there's the concept of installed base. For computers, this would be the ratio of one brand or platform that is currently in use compared to the total number of computers in existence. This gets a lot trickier to calculate, because computers are being retired all the time at uneven intervals, and the time they spend being used is also highly variable. Still, it's an important thing to consider for computer companies, especially if they are trying to break into an already-established market. It's great if you have a ten percent market share in the first quarter that you sell your new product, but what if the industry has been around for years and countless millions of a competitor's devices already dominate the landscape?

Many articles on market share confuse the two terms. Some report on installed base using surveys of small groups of users, or look at the server logs of a few websites, and then announce this as market share. Neither of these two methods is especially accurate, and can sometimes produce questionable conclusions. The only reliable way to measure market share is to painstakingly count up all the sales of every product in a single quarter (this article will primarily use this method).

The other place where confusion can reign is in cherry-picking the regions used to provide the data. Companies with dwindling global share will often point to countries where their sales are still strong, or report only retail sales if their direct channel isn't doing as well. To be fair to everyone, the numbers I am using are for worldwide sales through all channels. With that said, let's begin by returning to the early days of the "personal computer" revolution.

The personal computer (Triassic Period)

We tend to forget that the personal computing industry, a cornerstone of the modern world that sells hundreds of millions of units every year, was largely created by a few disaffected nerds in their garages. Established mainframe and minicomputer companies took years even to notice the personal computer. When they finally entered the market, they had decidedly mixed results.

The Altair―so fancy, it's displayed in a museum.

flickr user /dave/null/

The first true "personal computer" was the Altair, invented in 1975 by Ed Roberts. It established most of what came to define the industry: the desktop form factor with attached peripherals, an internal expansion bus for add-on cards, a third-party software ecosystem with Microsoft providing the primary user interface (which in those days was a BASIC interpreter), and various conventions and computer fairs where users and vendors could meet.

Because anyone could enter the market with very little startup cost, the early years of the personal computer featured a dizzying array of models. I once took a copy of a 1980 issue of Computers & Electronics and counted over a hundred different incompatible machines advertised inside. This Wild West landscape couldn't last for long. Most early companies failed to make the transition from garage to global business.

Four winners emerged from this early era: the Atari 400/800, the Radio Shack TRS-80, the Commodore PET, and the Apple ][. The latter was in last place for the first few years, until a happy accident gave it the industry's first killer app: the spreadsheet VisiCalc. The PET soon gave way to the VIC-20 and the enormously popular Commodore 64, the first personal computer to really make an impact on the mass market. It would go on to sell 22 million units, which would still be a respectable number for a single new computer model today.

The early market was also much more regional than it is now. The Sinclair ZX-80, ZX-81, and later the Spectrum sold well in their native United Kingdom, but made a smaller dent in the US. Similarly, the Apple ][ sold in much smaller numbers in Europe. The UK had its own unique ecosystem of computers, including the popular BBC Micro, branded after the national broadcaster.

The Sinclair Spectrum was the UK's equivalent of the Commodore 64.

Wikipedia

The young industry was shaken to the core when IBM introduced its own Personal Computer in 1981. The IBM PC, Model 5150, wasn't particularly impressive at launch. It was expensive, and while it did sport a 16-bit CPU capable of addressing up to 1MB of memory, it was underpowered, had no graphics capabilities out of the box, and had no sound chip. Compared to a much cheaper and more colorful Commodore 64, it hardly seemed like a contender.

Two things changed the fate of the IBM PC: the IBM brand name and the clones. Ironically, the PC was easy to clone mostly because it was so uncomplicated, and it was uncomplicated because it had been hastily designed from off-the-shelf parts to get to market before some other computer maker took the market away from IBM forever. It had no custom chips, just a CPU hooked up to some RAM and an expansion bus that was fully documented so that third parties could create add-on cards. The only proprietary bit was a simple chip containing the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) code that started the machine up and told all the parts how to communicate with each other. Even the operating system was off-the-rack, a hasty CP/M clone purchased by Microsoft.

Competition between the clones brought the price of the PC down, and add-on cards filled the gaps in functionality from the original model. The market story from 1981 to 1985 is largely about the PC―and we could call it a single market because the clones were absolutely, 100 percent compatible―slowly taking more and more market share. Other platforms, including the venerable Commodore 64, fell off.

Apple, Commodore, and Atari reacted to this Big Brother enemy of IBM and its army of clones with a new generation of 16-bit machines that vastly outstripped the PC in features. The Macintosh in 1984 brought a mouse and graphical user interface to the mass market (although initial sales were slow). The Atari ST added color and MIDI sound to the deal, and the Amiga in 1985 featured 4,096 colors, four-channel stereo sampled sound, and pre-emptive multitasking. These features were literally ten years ahead of their time.

The Amiga was ahead of its time but could not dent the PC juggernaut.

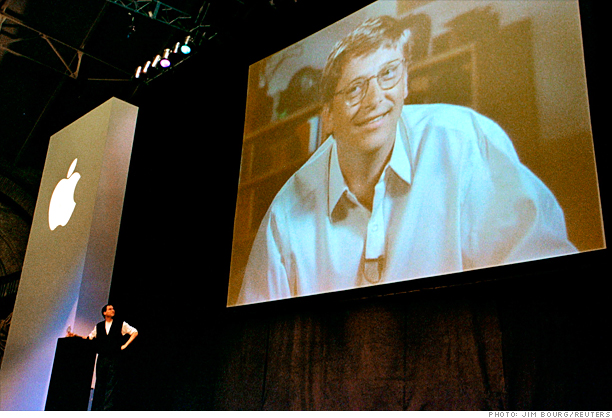

Sadly, for various reasons, these three platforms failed to make much of a dent in the continuing PC onslaught. Commodore went bankrupt in 1994; Atari was sold to JTS in 1996. While Apple did well in the desktop publishing market, their sales did not keep up with the rest of the industry, and the company was losing billions of dollars by 1997.

"The PC wars are over. Microsoft won," Steve Jobs said bitterly from exile at NeXT, his new company a testament to how hard it was to establish a new computing platform. Notice that he didn't say IBM won, something that everyone was worrying about back in 1984. By this time IBM had already tried and failed to recapture the market with its line of slightly more proprietary and harder-to-clone line of computers (called Personal Systems/2, or PS/2 for short). The only legacies of those machines that survive today are the small, round PS/2 connectors for keyboards and mice that remain on some motherboards.

The IBM PS/2 failed to recapture the market from the clones.

Wikipedia

The story from 1997 to 2003 includes the remarkable return of Steve Jobs to Apple, the introduction of the iMac and the release of OS X, and the NeXT operating system reborn in new, likable colors. What it doesn't include is an increase in the Macintosh's market share. The graphs for this period are boring: 97 percent PCs, 3 percent Macintoshes. Nothing else. But the seeds, encased in white plastic with a curious rotary dial, were being laid for a brand new industry that was about to revolutionize the personal computing landscape.

The Age of Mammals―smartphones take the stage

The idea of a portable digital organizer has been around for as long as the computer itself, but it wasn't until the Palm Pilot, released in 1996, that such devices became a part of modern society. The Palm Pilot was itself a re-imagining of earlier attempts by Go with the GridPad (1989) and Apple with the Newton (1993) to create portable digital assistants, or PDAs. The main differentiator of the Palm unit was its smaller size and simplified user interface. It was released in an era when mobile phones were just getting small and cheap enough to become commonplace. It didn't take long for people to start imagining that phone and PDA could be merged together.

The first smartphones were ungainly mutants, scurrying around in the underbrush of the computing landscape. IBM's Simon was shown as a concept product in 1992 and was released to the public a year later. It had many forward-thinking features such as a touchscreen and an on-screen predictive keyboard. Nokia was the first to combine an existing PDA with a phone―early prototypes had the two devices attached with a hinge.

There were dozens of different incompatible models in the early years, but by 2001 three platforms were taking the lead: Nokia's smartphones based on its Symbian operating system, Palm's line of PalmOS-phone hybrids, and Microsoft's Windows CE-powered smartphones.

An early Nokia smartphone running Symbian.

Wikipedia

I remember visiting a friend of mine who worked at Microsoft around this time; he handed me his Windows CE smartphone and breathlessly asked me what I thought of it. I recall feeling like I had travelled back in time: the user interface was clunky and the device was constantly running out of memory. Web browsing was incredibly slow, and most sites had difficulty even displaying. It was just like things had been with the early 8-bit computers: you could see that this was the future, but you couldn't honestly recommend the devices to anyone but the most hardcore geek.

This all changed in 2002 with the introduction of Research In Motion's Blackberry. Like the Palm Pilot six years earlier, it focused on a few things and tried to do them really well. The ability to send and receive e-mails on the go was a killer feature, and Blackberry became a global phenomenon.

iPhone changes the game

Everything changed with this little device.

Jacqui Cheng

The landscape from 2002 to 2007 looked similar to the slow rise of the PC from 1981 to 1985: phones running the Symbian operating system (used primarily by Nokia but also Sony Ericsson, Motorola, and Samsung) started to take a dominant share. Nokia was the darling of the tech industry, producing a dizzying array of smartphone models, each with more features than the last. In a solid second place was Microsoft with Windows Mobile, a rebranding of the Windows CE operating system. RIM's Blackberry took third place, mostly in the corporate market, but it also had a following of messaging-happy teenagers. The remainder of the market was split between phones running various versions of Linux and PalmOS, with the latter trailing off as Palm Inc. repeatedly split apart and merged back together again, changing strategies along the way.

Everything changed in 2007 with Apple's announcement of the iPhone. Like the Macintosh in 1984, it changed the game in terms of user interfaces: physical keyboards and styluses were out, replaced by a large capacitive touchscreen that was finger-friendly. Also like the Mac, it was available only from a single vendor, and initial sales were relatively modest, at least compared to the smartphone industry as a whole.

But the world in 2007 was different from the world in 1985, and the smartphone market was not the personal computer market. The iPhone was highly visible in stores and TV commercials. Early adopters easily made converts when they showed off their phones to their friends, most of whom did not yet have smartphones.

Competitors were caught flat-footed. The Samsung Jack, to give one example, was a contemporary of the iPhone and ran Windows Mobile 6.5. It had roughly the same hardware specs but instantly felt like a dinosaur in comparison. Google hastily altered development of its mobile Android platform from being a Blackberry look-alike to being an iPhone work-alike.

Android moves in

The fate of mobile phone platforms is inextricably tied together with the network carriers. While the iPhone was growing in popularity, it was still not available on all carriers (and in the United States, it was only available on one). The others needed a product to compete, and Android was the right platform at the right time. Google gave away the software for free, which is always nice, and worked hard with the telecom companies to make it available on as many phones as possible.

iPhone and Android eat away at everyone else.

As Android sales continued to rise, many pundits saw this as a repeat of the Macintosh and Windows story. Only Google was playing the role of Microsoft this time―Microsoft itself was stuck floundering with an obsolete Windows Mobile 6.5 and the rewrite, Windows Phone 7, was delayed. With Android available on dozens of different models from different manufacturers and the iPhone only available from Apple, it seemed like the Attack of the Clones all over again. Steve Jobs, already angry at Google for what he saw as "stealing" his ideas, decided to rewrite the script.

Check out my pad

Everything changed with this little device.

Jacqui Cheng

The iPad was a product that nobody knew they wanted until they had seen one. Initially derided as a "giant iPod touch" that was less capable than a similarly priced netbook, the iPad used the same interface and applications as the iPhone, making it easy to pick up and use. The form factor and long battery life―reusing iPhone components allowed it to be almost all battery―made it useful in ways that previous attempts at tablets were not.

What the iPad did to the mobile phone market, however, was more complicated and subtle. Because the devices (along with the iPod touch) shared the same applications, they expanded the ecosystem and rewarded people for owning both of them. Android tablets quickly followed, but their user experience was not quite up to par, and when priced similarly to the iPad their sales figures were abysmal. When buying a mobile phone, the carriers have a huge amount of influence on the sale. Tablets, however, have no such gatekeeper and sell only on their own merits. Attempts by RIM and HP to launch their own tablets crashed and burned, showing that the software ecosystem mattered as much or more than the technology.

The wild card in this battle was Amazon's Kindle Fire, an Android tablet with its own user interface and its own applications store (albeit a reasonable mirror of the Android app store). The low price and the Amazon name attracted many buyers, but unfortunately we do not know the numbers as Amazon refuses to release them.

Microsoft, as usual, was late to the party. The company decided its best bet was to re-engineer the entire user interface for the next version of Windows on the desktop to make it look and feel like a tablet, and then launch the tablet version on both Intel and ARM platforms. This is a sign that the company is taking the tablet (and mobile phone) market seriously, but it may already be too late.

The iPad came out of nowhere to dominate an entirely new category of device.

What personal computers can tell us about smartphones

While computers and smartphones are different markets in different eras, the history of the former may have something to teach us about the latter. We have already seen history repeat itself early on, with many different incompatible models dying off and only a few survivors remaining to fight over the market.

The survival of the Mac tells us that platforms can endure for many years with low (sub five percent) market share, as long as the parent company continues to invest in the product. This may be good news for Microsoft as it struggles with two to three percent share for Windows Mobile. The Mac also shows that major operating system transitions are possible, which is good news for both Microsoft and RIM.

However, platforms that continue to decline risk bankrupting their parent companies, as happened with both the Amiga and PalmOS/WebOS. While other firms may pick up the pieces, the shock of the transition is usually too much for the platform to survive. As platforms fall, so do the communities that develop applications for those platforms.

Network effects and the power of applications

As we saw with the personal computing market, once a platform reaches a certain level of market share, network effects kick in that strengthen the platform. Nobody ever waxed lyrical about the beauty or elegance of Windows, but everyone admitted that Windows computers were everywhere, were reasonably priced, and had vastly more applications available. No matter how tiny the niche, if an application existed in that niche, it existed on the Windows platform. Once this became an established fact, it never went away.

Right now, that kind of application ubiquity only exists on the iOS (iPhone and iPad) platform. If a mobile application exists, it will exist on the iPhone. If a tablet application exists, it will be on the iPad. Android comes in at a close second, especially for phones, but Windows Mobile is a distant third in phones and doesn't even exist yet in tablets. Microsoft is also in the uncomfortable position of having Android already claiming the position it held on the desktop. In this scenario, Windows Phone isn't the PC and it isn't even the Macintosh―it's the Amiga, only without that platform's technological advantages.

The future of the mobile platform wars

It is of course impossible to predict the future of the computing industry with any great accuracy. Nevertheless, we can look at trends and try to predict where things are going.

While Android has taken the majority share in mobile phones, the iPhone remains strong. The story in tablets is one of continued iPad dominance despite a multitude of competitors. The future is not likely to mirror that of Windows, which took a 95 percent share and never looked back. Instead, both platforms will continue to duke it out with neither gaining total dominance over the other.

It's not a huge stretch to imagine RIM and Nokia continuing their slide into niche status. RIM is in the middle of a difficult operating system transition and Nokia killed off its Symbian line of smartphones to switch entirely to Windows Mobile Phone 7, which has been a disappointment of colossal proportions. Windows 8 may change the game somewhat, but it will likely be too little and too late. Windows was never about the brand name―it was about ubiquity and application availability, neither of which will apply to Windows 8 tablets. It might simply be that the world has moved on.

The Post-PC era

When discussing the rise of mobile phones and tablets, it's common to talk about a "Post-PC" world. It's a phrase that Steve Jobs loved because it conjured up images of PCs as dinosaurs that had gone extinct, their beige bones bleaching in the sun.

PC isn't going away any time soon: 353 million PCs were sold in 2011. That's a massive figure despite a global recession, and it's the highest it has ever been.

The truth of the matter is that the PC isn't going away anytime soon. Sales figures show that the market may have flattened out somewhat, but it is still growing: 353 million PCs were sold in 2011. That's a massive figure despite a global recession, and it's the highest it has ever been. But surely this is the last hurrah of the PC now that cheaper and more mobile phones and tablets are taking the stage? Isn't it inevitable that the PC will dwindle and die out?

Technology journalists have a tendency to make excited pronouncements about certain technologies being "dead," and I'm just as guilty as anyone else. The truth is that technologies rarely if ever actually vanish from the planet. IBM still sells both mainframes (its System Z units) and minicomputers (the AS/400 line, which became Power Systems), and of course Microsoft Word is stubbornly surviving. Even the Amiga is still around!

However, while technologies don't often die, they can and do get confined to tiny niches that no longer affect the world as a whole. Print books will always exist, for example, and there will always be blacksmiths crafting horseshoes. Whether or not the traditional PC will live on as a utility truck or a horse-drawn buggy has yet to be determined.

Acceleration

One notable difference between the PC market and the smartphone/tablet market is the accelerated time scales that mark their evolution. This is most dramatically visible when we graph unit sales rather than market share, and use a logarithmic scale for the units so that the vastly different scales of the original PC industry and the current one can be easily compared.

Comparison of personal computer, smartphone, and tablet sales.

If it seems that the world is moving at a faster pace than it used to, that's not just a side effect of being a nerd moving into middle-age. Technologies are actually developing at an accelerated rate, something that Ray Kurzweil spent an entire book painstakingly documenting with an endless series of logarithmic graphs. The end point of such acceleration is unknown―it may start to taper off, as human population growth is doing. Or it might be a sign that we're rushing toward a point where technological power becomes essentially infinite and all bets are off. Behold―the Singularity!

In any event, it pretty much guarantees that the mobile devices we have a decade from now will be unbelievably sweet.

| }

|