Smart Body, Smart World: The Next Phase of Personal Computin

Source: Sarah Rotman

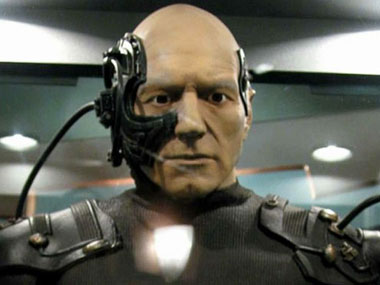

In the past half-century, computing has evolved from the mainframe to the desktop to the shoulder bag to the pocket, and now it’s taking over new frontiers: our physical bodies, and the physical environments that we inhabit. The next wave of growth in personal computing won’t come from PCs (obviously) or even phones, which have already reached nearly ubiquitous adoption. It will come from sensor-laden devices that take many shapes: glasses, contact lenses, tattoos, wristbands, shoes, textiles, toothbrushes, mattresses, mirrors, thermostats, doorways, steering wheels and parking spots are just a few of the nearly infinite possibilities. Sometimes these sensor-laden devices are called the Internet of Things, but I don’t think that fully captures the phenomenon I’m describing. I call it “Smart Body, Smart World,” because the devices themselves (the “things”) are not the point ― it’s about the data they collect, the way the data is interpreted, and the smarter decisions we make when we have access to these sensor-sourced data and insights.

In the past half-century, computing has evolved from the mainframe to the desktop to the shoulder bag to the pocket, and now it’s taking over new frontiers: our physical bodies, and the physical environments that we inhabit. The next wave of growth in personal computing won’t come from PCs (obviously) or even phones, which have already reached nearly ubiquitous adoption. It will come from sensor-laden devices that take many shapes: glasses, contact lenses, tattoos, wristbands, shoes, textiles, toothbrushes, mattresses, mirrors, thermostats, doorways, steering wheels and parking spots are just a few of the nearly infinite possibilities. Sometimes these sensor-laden devices are called the Internet of Things, but I don’t think that fully captures the phenomenon I’m describing. I call it “Smart Body, Smart World,” because the devices themselves (the “things”) are not the point ― it’s about the data they collect, the way the data is interpreted, and the smarter decisions we make when we have access to these sensor-sourced data and insights.

Why is this happening now? Smartphones, which will make up nearly half of mobile phones in the U.S. by the end of 2012, enable “app-cessories” like the larklife or the Fitbit to do a lot with a little: The phone provides processing power, display and cloud connectivity. Smartphones like the iPhone 5 and many Android phones, as well as all Windows 8 devices, have native support for low-energy Bluetooth (they’re “Bluetooth Smart”), which allows sensor-laden devices to transmit data to the phone using very little battery. It’s not just the hardware that’s evolving, it’s also the software: Programmers are getting more sophisticated at creating algorithms that interpret the sensor-collected data and deliver advice. For example, start-ups Lark Technologies, Live!y, and Wallet.AI all consult with cognitive science experts to create products that will actually change people’s behavior.

Consumers seem receptive when there’s a clear benefit that they get in exchange for their data. Progressive Casualty Insurance, for example, has more than a million users of its Snapshot device, which tracks real-time driving behavior (acceleration, breaking, mileage, time of day) and adjusts consumers’ auto insurance policies based on their actual risk; on average, users save $150 per year on their policies, according to the company. BodyMedia reports that its Fit armbands, which track 5,000 data points per minute via four sensors, have an average length of use of six months and climbing, and are used not only for losing weight but also for managing chronic diseases like diabetes.

Moving sensor-laden devices from niche to mainstream requires solving data-related problems, such as unlocking and sharing data from multiple sources, including hard-to-get data from healthcare providers. Products also need to improve data reliability: For example, Nike+ FuelBand users have noted that they get more “fuel” points for arm-intensive (but not fitness-inducing) activities such as eating pizza than they do for walking up a flight of stairs. Add to that the privacy and security challenges of managing personal data. Putting users in control of their own data will be a key success factor for any Smart Body, Smart World product. Consumers may enjoy sharing their activities with their social networks (or subsets of their social networks) some of the time, but also will want modes that act more like private journals than public broadcasts.

Smart Body, Smart World products will reorder the value chain of consumer electronics. The primary beneficiaries will be the algorithm owners; hardware design is important, but the core IP is in the algorithms that interpret the sensor-collected data and deliver advice. The platform owners, namely Apple and Google, will be the secondary beneficiaries; Google is developing first-party hardware (Google Glass and, reportedly, an Android smartwatch) while Apple is cultivating an ecosystem of apps and accessories. Carriers will accrue value through increased use of smartphones via sensor-laden accessories, and to a lesser extent via standalone device connections. Retailers also stand to benefit from smart product growth ― but not traditional consumer electronics retailers. Sensor-laden baby mattresses would be an easier sell at Diapers.com or your local baby goods store than at Best Buy ― consumers will look for these devices at the retailers that solve the greater lifestyle challenge, not the retailers that specialize in electronics.

It’s hard to overstate how different out lives will be when the Smart Body, Smart World paradigm is in full force. For consumers, the effects are likely to be both positive and negative: With more information and guidance, humans can make more “rational” decisions, but if we are always listening to our devices, we may experience less spontaneity, too. And what happens to our nervous systems when devices surround us, even when we sleep? Those questions are beyond the purview of the type of strategy research we do at Forrester, but answering them will be crucial to living in a Smart Body, Smart World paradigm.

| }

|